The full original article can be read in Hebrew here on MAKO.

Verbit, which has developed a transcription solution based on Artificial Intelligence and human factors, is now working on transcribing the testimonies of Holocaust survivors. The results can already be seen online, including parts of the testimony of Tuvia Bielski, who was the commander of a battalion of Jewish partisans in Belarus.

“We saw a special challenge in transcribing very old recordings which were low quality. We also felt it was an important mission of ours to do so,” said Tom Livne, CEO of Verbit.

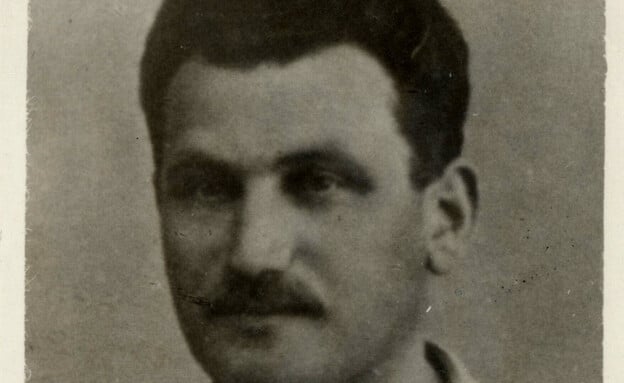

Tuvia Bielski | Photography: Photo Archive, Ghetto Fighters’ House

As each year passes, the number of living Holocaust survivors dwindles. One of the biggest challenges is preserving the memory of the Holocaust even after they are no longer with us. Verbit, which develops digital transcription solutions, is now partnering with the Claims Conference and their preservation efforts by transcribing millions of minutes of survivor testimonies in different languages.

In the archives of the Ghetto Fighters’ House, transcripts recently compiled by Verbit of decades-old recordings, some from 40-50 years ago, now feature the testimony of Tuvia Bielski, commander of the Jewish partisan battalion in Belarus, which was given in the 1970s.

With this transcript, now individuals and future generations can learn about his unique story.

Exploring one archive being transcribed

Bielski was born into a Jewish farming family in the village of Stankiewicz near Novogrudok, Belarus. At the age of 17, he joined the pioneer movement. In 1928, he was drafted into the Polish Army and reached the rank of corporal. In 1930, he married, settled in the town of Subbotnik and owned a fabric shop.

In June 1941, when the Germans occupied the area, he returned to his native village. After his parents and family were murdered in the Nowogródek ghetto, he fled with his brothers, Zosia, Asael and Aharon, to the forest. The brothers obtained weapons and established a partisan group of 17 men in the forest. Most of them were members of the Bielski family, and Tuvia was chosen as the group’s commander. Tuvia sent emissaries to the surrounding ghettos and invited the Jews imprisoned in them to join his group. Hundreds heeded his call.

Bielski and his men became famous for their acts of revenge against the Belarusian policemen and peasants who murdered Jews and collaborated with the Germans. Tuvia’s battalion was not a partisan battalion in the usual sense. It bore the character of an organized Jewish community. In his compound, there was also a synagogue, a court, a children’s school, a clinic and other communal institutions.

In the summer of 1943, the Germans launched a large manhunt in the Naliboki forests, with the aim of eliminating Soviet partisan fighters, especially Bielski’s battalion. The partisans retreated deep into the forest. Tuvia was ordered to leave only single men carrying weapons in his unit. Meanwhile, families, women and children were to leave the area. Tuvia, who knew that this order would doom these men to death, did not obey it. He retreated with all of the men in the battalion, with the combat between his men covering the non-combatants. He brought them out safely from the encircled forest.

When the area was liberated by the Red Army in the summer of 1944, 230 men entered the city of Novogrodski.

In 1945, he immigrated to Israel with his two surviving brothers. In 1954, he immigrated to the United States. After his death, he was buried in Israel.

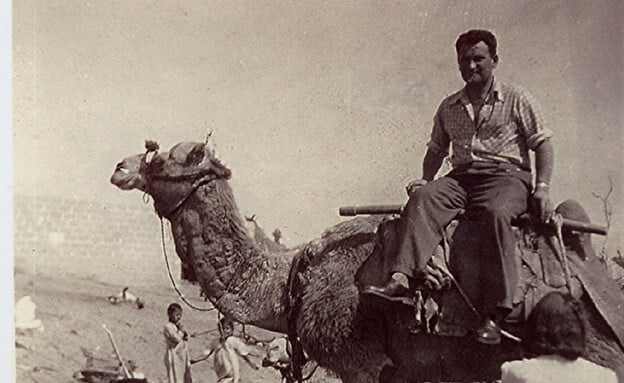

Tuvia Bielski| Photography: Photo Archive, Ghetto Fighters’ House

Portions of Bielski’s testimony, taken from films produced by the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, can be heard and read on the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum website.

Verbit’s collaboration with the Ghetto Fighters Archive stemmed from its business relationship with the Claims Conference, a global organization that works to ensure the welfare of Holocaust survivors. It handles, among other things, the transfer of compensation from the German government to survivors.

How is the transcription of these testimonies done?

“A machine makes the initial transition, after which a human layer is added that makes corrections and leads to a high accuracy level of transcription which can be used by the archives for their needs,” explained Tom Livne, CEO of Verbit.

Livne recently made headlines as one of the most prominent opponents of the legal revolution in hi-tech.

“The amount of time it takes to produce transcription varies as a function of file quality, background noise, certain local dialects and more,” he said. The archives gave us a list of ghettos and a glossary of terms relevant to the period, so that our transcription work can reach an even greater accuracy level in its initial stages.”

This project led Verbit to establish a community of Hebrew-language transcribers who are familiar with Yiddish concepts from the Holocaust period. The main languages which the testimonies are translated to are Hebrew, Yiddish, French and English.

“Our company does transcription with Artificial Intelligence, and here we saw a special challenge in transcribing very old recordings which were not high-quality, alongside a sense of mission and heritage of the people of Israel,” said Livne.

While Livne himself has no personal connection to the Holocaust from his immediate family, he said such a project presents a “national mission.”

“We believe this will make it possible to protect and preserve survivors’ testimonies, exposing their stories to a larger global audience and in a variety of languages,” he said.

Verbit’s team works closely with the non-profit Claims Conference and its team to produce this important transcription work.

“Unfortunately, in the not too distant future, we will have to tell the story of the Holocaust in a world without survivors,” said Greg Schneider, Senior Vice President, Claims Conference. “Their testimonies should be treated as the most sensitive material.”

“Despite technical challenges, such as poor audio quality and diverse dialects and accents, transcription must be accurate,” Schneider said. “Verbit understood the need for precision and the historical importance of such work from the early stage of the project.”