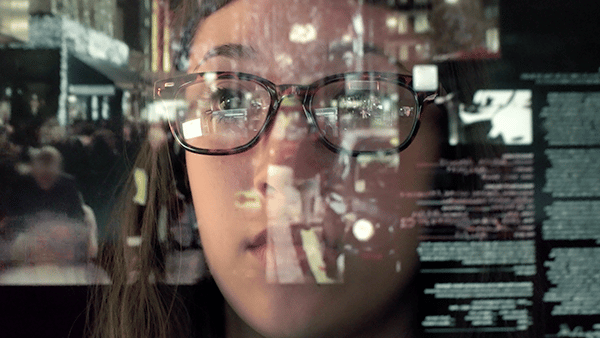

About 50 years ago, college freshmen were expecting protests and poetry on campus, and 30 years ago, they may have been arriving ready to step into a management class and a fraternity bash. Looking back at this decade, it is likely one thing will be seen as the theme for the young people of college age: technology.

From a fascination with selfies and gaming, to keen interest in robotics and their own sophisticated startups, students today are focused on tech—and it has reached deeply into the way they are taught and learn. For instance, some research suggests 60 percent of college students use their phones to study, and popular “Edtech” conferences overflow. One expert recommends colleges find their most scenic spots and highlight them for Instagram messages during recruiting tours.

So, professionals who work with students as they explore and select colleges—and even consider new options that offer them entire degrees through their screens, need to keep up, experts say.

From his perspective as counselor at a school that stresses student involvement with technology, Adam Lindley said students moving on to college expect both new high-tech tools and new ways of learning.

“Our students are digital natives, having used technology since they started their education. They have come to expect it in education too,” Lindley said. And these changes have led them to consider new fast-changing majors—things like social media manager, game designer, and cybersecurity professional, he added, noting that colleges have to adjust.

Colleen Kaplan, technology integration specialist at Lindley’s school, St. Francis High School (IL), said there are broader changes in the way students think about learning.

“With the advances in technology, rote memorization of facts and ideas is not nearly as important as the ability to look at a problem and figure out the best way to solve it,” Kaplan said. Employers increasingly look for students with those skills—and more students and parents have come to understand that and expect a college experience that hones them.

And students are simply learning online more often.

Screen Sessions

“An ever-increasing number of pre-college students have access to online learning and, if not directly requesting college credit for such learning, they and their parents will likely expect online learning to be part of their college educational experience in some way,” said William Conley, vice president for enrollment at Bucknell University (PA), who has studied tech-fueled changes in K-12 education.

Peter Smith, an endowed professor studying innovative practices in higher education at the University of Maryland University College, a former president of two colleges, and author of a new book on the future of college in the digital age, also says students will increasingly want to know what a college offers in connection with new technology.

“There now is not one specific type of educational experience for these students—and their expectations can be very different,” Smith said. “I would say if I was in admission or working with students considering college, I would want to understand their expectations and clearly articulate what they can expect in terms of pedagogy, technology, and resources offered at a school.”

Conley noted that not only are high school students opting to take online classes, schools in nearly every state have some offerings, more than half the states have full-time online high schools, and a number of schools require students to take at least one online course to graduate.

While in some cases fully online high schools have struggled, One Schoolhouse has grown to offer 60 courses for 136 independent schools and Stanford Online High School has become a sought-after option for talented high school students, last year graduating about 74.

High school students’ experiences with education technology may vary widely according to their school but will regardless involve the use of more technology as it seeps into most school functions—from instruction and homework to behavior monitoring and credit for their work.

*****

Understanding Tech

Apart from the technology in K-12 schools, professionals working with college-bound students should understand the tech at their school. Here are a few things they should think about that will be of interest to prospects.

The basics. Can you make the availability of cell phone and wi-fi service a selling point or clearly explain about such access if asked? Obviously, it can be a critical issue for students today. What about hubs and interactive displays? What about labs or workstations or pods where small groups of students can work together? Services or centers that can help with tech issues? Are there specific spots on campus for those truly interested in the most advanced tech—and are professionals available to guide them?

Online options. What sorts of credits from online sources does the college accept and what online options does it offer? What are its policies about blending the two?

Open learning. It can include classes that are free and available to anyone and even “open pedagogies” where student’s work is shared outside the open classroom, challenging students to make it valuable more broadly.

Open resources. Concerns about the spending on average over $1,200 on textbooks might prompt questions about the use of Open Educational Resources (OER) on campus.

Classroom platforms. What does the faculty use for its communications with students, for collaboration and for the flow of work? Are applications such as Google Docs and Slack commonly used? What about video-conferencing?

Social media. How does the institution participate in social media? What are its policies? How do interested parties participate? One expert suggests that colleges promote their locations that will look best and represent the college well on Instagram—especially during the college visit, when they might be recommended.

Research options. Students and families should be made aware what research is going on and will be needed in the future at the college. They should understand how the college research services will be of use and what research access they can access offsite.

*****

Top Approaches Go Digital

Specific initiatives that are popular in school more often are connected firmly to technology.

Project-based learning, for instance, which is a major theme in K-12 education, is increasingly accomplished online with a steady stream of new applications. Students today will graduate having experienced that pairing and expect it in college, said Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education. She recently described the direction for public education that colleges should anticipate.

“The experience with personalized or project-based learning online has varied, but it is happening and kids have an expectation that their schools will be tech-savvy as they approach all new ways of learning,” Lake said.

Susan Nash, an educator and education technology expert who writes about the intersection of the two, said technology has boosted other initiatives in the classroom from which most students will have benefited. Collaboration, for instance, can take place as students explore work together with easy guidance by an instructor—in classrooms where a “one-to-one” ratio now means a device for every student rather than personal attention.

The decades-old push to differentiate in the classroom, with variations like personalized or individualized learning, has gotten a significant boost as students go online to move ahead or get additional support when they need to.

Also, “blended learning” is increasingly popular in schools within a class or with some entire offerings online, Smith said, and “flipped learning” is growing in popularity, where students learn subject material online and at home, then work on the lessons in class with the teacher’s support.

“Some sort of blending is the direction schools are headed,” Smith said, “and it is proving to be a richer, more successful learning environment.”

Jon Bergmann, considered one of the founders of the flipped learning movement and one of its key advocates, notes that colleges should expect every student soon will have had that classroom experience and perhaps prefer it over the long lecture in a stadium-like classroom.

Arizona State University has had success with an approach that is similar. Students work independently and a blend of artificial intelligence and adaptive technology measures their progress, evaluates them, and adjusts the work. In class, students interact with teachers in “higher order” work. Entire classes and programs of study are aligned and based on the structure, and such alignment and interdisciplinary work with online exploration is increasing in K-12 classes.

Comfort and Careers

Sarah Linehan, director of admissions at the State University of New York Adirondack, a community college in rural northeastern New York near the Vermont border, said her students come with an ever-growing relationship with technology.

“They develop a comfort level with this learning format before they ever set foot on a college campus,” Linehan said. “With so many competing priorities, such as intercollegiate athletics, jobs and extracurricular commitments, students inquire about the option right away. Online learning is an alternative that is more conducive to their busy lifestyle.”

Dual-enrollment classes are continuing to grow in popularity and more often provided online, according to Conley, and the International Baccalaureate program has online courses, along with Advanced Placement programs at some schools. MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) are available to K-12 students, and some high school students expect they will offer college credit.

Lake and CRPE also advocate for entirely new ways of establishing competency, which includes students being able to obtain credits in a system that blurs the lines between grade levels in high school and college, fueled by new options online.

As two experts described them in Inside Higher Education, “over a lifetime of learning, individuals can assemble, or stack, a series of traditional degree-based and/or nontraditional credentials—certificates, certifications, licenses, badges, apprenticeships and more—that recognize achievements and provide an accurate assessment of knowledge, skills, and abilities.”

Such stackable credentials are increasingly an option, and often they will be obtained online. There have been indications that The College Board is working to develop a way of becoming a third party that could oversee online credentials.

Lake said colleges should prepare for a greater emphasis both in high school and higher education on new ways students are using the Internet to more thoroughly explore careers, which, she said, is badly needed and long overdue in K-12 and higher education.

First, that might mean students will expect high school counselors, college admission offices, and career centers to have the resources and know-how to help them find good resources, including an array of new online interest inventories and other career exploration platforms.

Also, colleges should expect that students will come with clearer and broader information about the careers, having had access to such new specific technology. Internet access alone and the speedy flow if information—and their comfort with it—also should provide them with more avenues to understand careers, and they will expect details about college offerings.

“These students will be self-aware, and they will know how to find out information about the fields they may want to pursue,” Smith said. “Admission offices should be prepared for them and their families to have very specific questions about the programs their college offers and the ways the institution will help them pursue them.”

For an Extra Boost

Assistive technology is also changing rapidly and professionals working in the college admission pipeline can expect that students will ask about a wide range of new devices and services.

Tom Livne, the CEO of Verbit, a company that offers high-tech transcription services to provide closed captioning in real time in college classrooms, said that services such as his are critical for universities to avoid violating federal law covering persons with disabilities, and because the new technology is faster, cheaper, and more accurate.

He sees colleges needing to consider initiatives that make speech recognition and transcription services and classroom close captioning readily available, although experts also note that students often have new technology on their devices and colleges simply need to accommodate it.

“When the entire learning process depends on audiovisual materials, speech technology like transcription and caption tools are key elements of the learning process and essential for a student’s success,” Livne said.

The College of Eastern Idaho has experimented with a device that allows deaf and hearing impaired students to see a miniature interpreter on the corner of a special set of glasses who hears the lecture online and signs. The session can also be recorded.

Livne noted that in a culture that has come to accept technology such as Google Assist and Alexa, new students will expect increased use of digital assistants. “They enable tremendous opportunities for educators and students alike by providing access to a wealth of information on any topic, simply by speaking a few words.”

And for admission offices specifically, impatient students who expect answers quickly might expect interactive and up-to-date websites and automated “chatbots” that handle routine questions quickly without human involvement.

Clearly, to work effectively with these students, admission offices need to understand technology in relation to the individual students, their performance and skill with new tools, and how their experience and expectations about education tech fits on each campus.

Jim Paterson is a writer and former school counselor living in Lewes, Delaware.